Quantock Dreaming

Secret mappings and mapping secrets in the Quantock Hills

Quantock Dreaming

Secret mappings and mapping secrets in the Quantock Hills

Spectral Traces - Fire in the landscape (AL)

An early poem of Coleridge’s speaks of “fire-clad meteors round me whizzing fly” and

“Thus like great Pliny in Vesuvius’ fire,

I perish in the blaze, while I the blaze admire”

STC did visit Naples & Vesuvius (and also climbed a firey Mt Etna) some years later:

"Sunday, December 15th, 1805.

"Naples, view of Vesuvius, the Hail-mist--Torre del Greco--bright amid

darkness--the mountains above it flashing here and there from their

snows; but Vesuvius, it had not thinned as I have seen at Keswick, but

the air so consolidated with the massy cloud curtain, that it appeared

like a mountain in basso relievo, in an interminable wall of some

pantheon."

The associations with the element of fire within Quantock Dreaming are increasing in number, to the point of becoming one of the ‘golden threads’ through a mass of sensory and research input. (“Fire walk with me”). In the surveying and imagining modes, many seductive paths are followed, but few are chosen. There are of course no true dead-ends in all this, only some paths where the going gets heavier (or lighter). Go n-eiri an bóthar leat...the bidding to the traveller in Ireland, that the road itself may rise to lift you up the incline....

To stick to a ‘fire’ analogy, there is firstly an intuitive locating of the campfire spot, then a phase of gathering of fuel, selecting and arranging the kindling, tending the delicate flame, encouraging, sheltering, until the fire takes hold and the heart(h) grows. For me, this echoes the creative-process sequence: intuition->imagination->creativity.

The traditional (and still contemporary) beacon fires on the high-points of the Quantock Hills were mirrored by our own midnight equinox fire on Dowsborough Hill (there are also maybe echoes of a fiery dragon local to here? The Great Worm of the nearby Shervage Wood...). Noted beacon occasions in the Quantocks have been the Queen’s golden jubilee (2001) and Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee in 1897.

William Phelps (Vicar of Bicknoller, 1811-54) described the east entrance to Dowsborough: ‘Here are three pits or hollows formed of stone, fifteen feet in diameter, and five deep; evidently sites of fire beacons; considerable heaps of stones on the same spot, indicate building to have stood there’

Some of the ‘peaks’ in the Quantocks have Beacon names - Beacon Hill, Kingston Beacon, Hurley Beacon, Fire Beacon Hill, etc. A Beacon Tower used to stand on Cothelstone Hill.

"Not far hence on the hill side to the south is the hearth of an ancient beacon, the only one still known as the "fire- beacon " by the folk. It is placed in the one position whence it is possible to see eastward the great ridge of Longdown, in Wilts, at the head of what was. once Selwood forest, while at the same time its fires would be unseen from anywhere on the nearer hills' across the Parrett. The beacon was evidently planned for communication with a gathering at some point close to Longdown ; and a point close by that hill having been the meeting place of Alfred's forces before the decisive battle of Ethandune, it is probable that hence he and his earl, Odda (whose name "Hodder's combe" preserves even yet), kept up communications at the time, unknown to the men of Guthrum who were gathered at Edington on the Poldens. There are many other beacon sites on the Quantocks, but some such specially remembered use of this one has fixed its name in the memory of the countryside."

Beatrix Cresswell, 1904

Bronze-Age barrows were modified when used as the site of fire-beacons by deepening the usual robbers holes in the top of the mounds to give some protection from the elements. Remains of cremation burials are numerous and associated with the barrows and cairns, whilst the practice of depositing charcoal in pits is also suggested. These Bronze-age rituals have been compared to Homer’s description (in the Illiad) of the burial of Patroclus by Achilles, paraphrased here by Hazel Riley:

“Mules and men with axes and stout ropes are sent to fetch wood, which is stached in a huge mound. A large procession of warriors, charioteers and horsemen forms and those closest to Patroclus carry his corpse, which is covered with locks of their hair. The corpse is laid on top of the pyre, then sheep and cattle are killed, their fat is used to cover the corpse, and the animal carcasses are piled around. Jars of honey and oil are added, so are four horses, two of Patroclus’ pet dogs and a dozen Trojans. throughout the night, as the pyre burns, Achilles keeps a vigil, pouring out libations, weeping, and walking around the pyre. In the morning the fire is extinguished with sparkling wine, then Patroclus’ bones are collected and placed in a golden vase, which is sealed with fat. The barrow is designed by laying down a ring of stone revetments around the pyre and earth is piled up inside. Finally, Achilles holds lavish games in honour of his friend.”

Swaling (controlled burning) of the heathlands takes place on the Quantock common and very early in the project I was struck by the sculptural qualities of the fire shovels to be found at positions (fire points) around the hills. Then there was local man John De Stogumber who was involved with the trial and execution of St Joan of Arc he was supposed to have cried "Into the fire with the witch" and helped to push her into the courtyard where the stake awaited her. Only after the event to be heard shrieking "I will go pray among her ashes”.

Pyrolysis...

At the end of our Holford Brook ramble, we encounter some more firey traces. At Kilve there is the intriguing remnant of Forbes-Leslie’s efforts to extract oil from the stones (oil-shales). One of the ruined processing buildings (The Oil Retort House) remains. In a similar geological vein, Kilve Pill, where the stream from Holford runs into the sea, was once a tiny port, used for importing culm, an inferior type of coal which was used in the many local lime kilns. Elsewhere in the hills, wood and charcoal was used for fuelling the kilns.

Here’s the English Heritage record of the Kilve oil shale building, in all its studious detail:

“ST14SW KILVE CP KILVE PILL 5/125 Oil Retort House - - II Oil retort house. Circa 1924. Red brick, irregular bond, and cast iron. Roughly square in plan, a rectangular block about 4 metres high and 2.15 x 2.45 metres square. Flat roofed, divided by recessed string course with inset cast iron bar on East front, corbelled projection below on all fronts, irregularly placed square ventilation holes, majority on East and West fronts; segmental headed loading opening on West front at ground floor level with cut off pipe above, angled segmental headed opening on North front above low external stepped plinth partially damaged. Surmounted by cast iron chimney with flange attached on West side, thought to have been an attachment to carry away and condense the vapours, in all about 5 metres high. In 1916 it was discovered that the shale beds of the North Somerset coast were rich in oil and in 1924 Dr Forbes-Leslie founded the Shaline Company to exploit them. This retort house is thought to be the first structure erected here for the conversion of shale to oil but the company was unable to raise sufficient capital and this is now all that remains of the anticipated Somerset oil boom. Listed primarily for historical interest.”

KIlve also has a ruined Chancery:

"Kilve in old times was a rare spot for smugglers. The pill (or pool) near the sea shore, the church tower, an the chantry, all served as places for concealing kegs o

wine and spirits. It is said that the destruction of the chantry buildings by fire in 1850 was aggravated by these spirits igniting." Beatrix Cresswell, 1904

The records of charcoal-making in the Quantocks are particularly interesting. This ancient activity was still happening in the early decades of the 20C (near Over Stowey). On our many walks through Holford Combe, the element of water has, of course, been paramount. Yet, we were, unknowingly, walking through the spectral traces of fire. According to English Heritage, nearly 100 charcoal-burning platforms have recently been identified in Holford Combe and the nearby Hodders Combe.

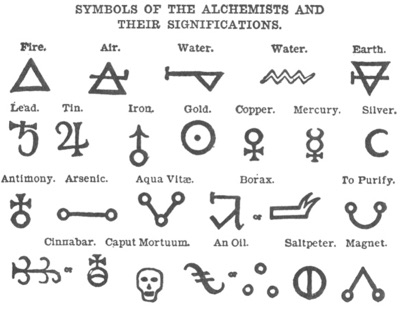

The Firey Furnaces: From ancient times, there are local records of mining and smelting - copper and iron. Close to Fyne Court, we find the place-names ‘Kingslode’ and ‘The Loads’, indicating past mining, and at nearby Volis Hilll are the remains of iron working - small hearths with roasted iron ore, charcoal and slag. Bronze would have been smelted locally.

Again from English Heritage:

“Doddington Former engine house at ST 1752 4009 - II Engine House. 1820. Rubblestone brought to course; roof removed. 2 stages, the upper stage recessed. Timber lintels to openings. Gable has a wide central entrance with round brick arch; above it a blocked opening to each stage. A window opening to one side wall and a window and two altered doorways to the other. The Engine House was erected in connection with a copper mine at Doddington, Holford. The steam-raising plant is thought to have been located in a less permanent lean-to structure adjoining the Engine House. In state of dereliction at time of listing”

"...Fyne Court, where lived Mr. Andrew Crosse, noted for his experiments in electrical chemistry, which were really the beginning of all our modern discoveries in the powers of electricity." Beatrix Cresswell, 1904

South at Fyne Court (another focal site for this 'Dreaming' project), Andrew ('The Wizard') Crosse worked a copper mine near Kingston St Mary, and built electrical machines and batteries in the dark cellars under his house. He strung up long lengths of copper wire in the trees near the house to capture ‘atmospheric electricity’ and relay it to his main laboratory (The Music Room...now Andrew Crosse Hall). During thunder storms, “the 5 large windows were lit up by brilliant flashes and continuous reports like cannon occurred”, “7 or 8 tables which filled the area of the room with extensive voltaic batteries of all forms sizes and extents....some were in porcelain troughs of the usual construction, others cylindrical, some in pairs of glass vessels with double metal cylinders beside them, others of glass jars with strips of copper and zinc. Altogether there were 1500 voltaic pairs at work...and in other rooms 500 more....he is in most cases his own manipulator, carpenter, copper smith etc.”

With the focus still on Fyne Court, the element of fire comes even more to the fore at a later date. The main house burnt down in an accident in 1898. It was never re-built, but the music room (the laboratory of Crosse) and the library survive.

No time to dwell much on other burning matters - e.g. the medieval pottery kilns of Nether Stowey, gunpowder production at Taunton, the glassworks and brickworks of nearby Bridgwater, the reactors at Hinkley Point?...even the light/fire-filled carnival of nearby Bridgwater, with its fantastic squibbing. (Is there more than a hint of a contemporary take on age-old seasonal fire rituals - the sacred bonfires of Samhain and the other Solar fire festivals of Solstices and Equinoxes?). Not forgetting also that Coleridge hailed from that other centre of ceremonial fire in the South West; Ottery St. Mary. No time either to explore the recorded quarrying of green igneous (firey) volcanic stone near Over Stowey?

(but there is a relevant Beatrix Cresswell quote: "At Hestercombe there is a

quarry, now, I believe, disused, where the slate joins a granite dyke, the granite being locally called " pottle- stone,")

Finally, the recorded practice of turf-cutting for fuel (Turbary), in the Quantocks is a strong link to my Irish homeland, where it is still widespread.

3 July 2008